A Heralded Mentor

Okay, what do G.K. Chesterton, C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, Lewis Carroll, John Ruskin, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Walt Whitman, and Madeleine L’Engle have in common? All friends of or influenced by one George MacDonald. Indeed, Lewis Carroll admitted that he might not even have submitted his Alice in Wonderland classic for publication if MacDonald, whose children loved Carroll’s manuscript, hadn’t encouraged Carroll to do so. No less a literary giant than C.S. Lewis credits MacDonald with being Lewis’s own master, whom Lewis wrote he quoted in nearly every one of his own classic books and who continuously carried Christ’s Spirit as much as or more than any other writer.

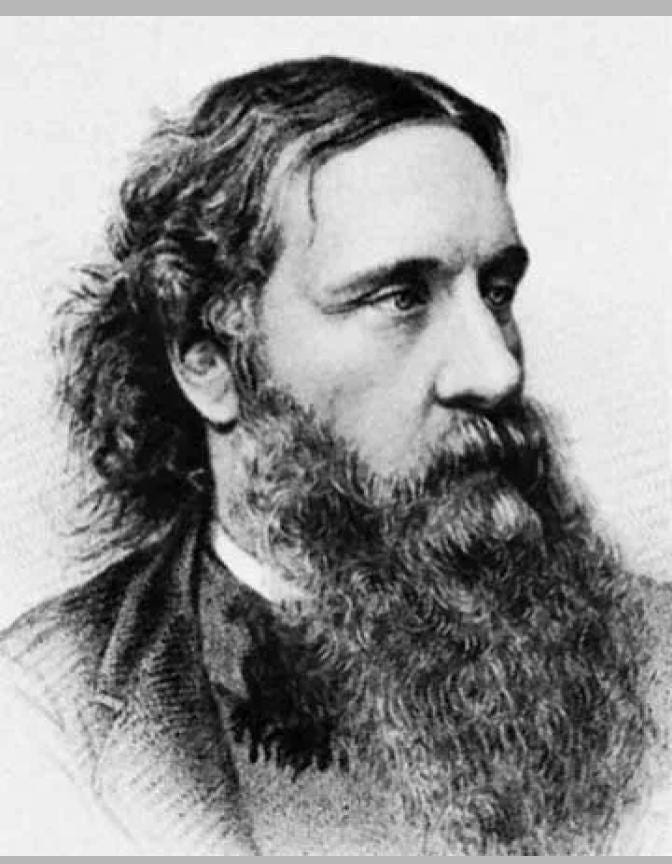

But Who Was George MacDonald?

So who was this mystery man? Perhaps George MacDonald is no mystery to you. You may have discovered him through Lewis, Tolkien, Chesterton, Carroll, or another of your favorite writers, which is how I discovered him. Isn’t that the way some of the best writers and thinkers come to us, with more-popular writers admitting that they stand on the hidden figure’s shoulders? MacDonald was born in 1824 in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, into a farm family oddly filled with scholars, particularly around the Celtic mythology and poetry that saturated the surrounding shire. From that one hint, you may already sense roots of Lewis’s Narnia and Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. MacDonald, in his day an extraordinarily popular and prolific author of serial Scottish highlands novels, was the conduit for a magical heritage of saints, goblins, and fairies.

It’s Often Hard Getting There

The route deep into one’s calling is often circuitous, isn’t it? It was for MacDonald. MacDonald got a great education, graduating from Aberdeen’s ancient King’s College with a degree in physics and chemistry. But he languished for three years before pursuing ministry training. Two years later, he was leading a church in England, the members of which didn’t care much for his preaching. MacDonald also contracted tuberculosis when young, a disease that felled his mother, two brothers, and three of his own children. The breathing issues with which the disease left MacDonald required his frequent movement in search of drier air than his Scottish and English homes offered. MacDonald left another brief pastorate in England for Algiers, hoping to regain his health. MacDonald eventually wrote nearly half of his corpus from a Mediterranean seaside British expatriate village, where he held court in a literary studio he founded there.

A Writing Career Blossoms

MacDonald was in his mid-thirties by the time he began writing the works for which he later became widely known. He wrote his faerie romance Phantastes in 1858. He published his first realistic novel David Elginbrod in 1863. when he was nearly forty. His best-known children’s serial At the Back of the North Wind (1868-1871), children’s fantasy novel The Princess and the Goblin (1872), and adult fantasy novel Lilith (1895) all came much later, as did his popular rags to riches Christian novels Malcolm (1875) and Sir Gibbie (1879). MacDonald’s widely celebrated fairy tales The Light Princess (1864), The Golden Key (1867), and The Wise Woman (1875) came in between. MacDonald’s writing career didn’t blossom in the spring, nor entirely by mid-summer, but more in the late summer. The wonders of MacDonald’s voluminous writing, though, eventually crossed the seas, where in 1872-1873 he traveled to tour for lectures arranged by the Boston Lyceum Bureau.

A Moving Encounter

George MacDonald gripped, held, and moved me just when I needed it, which is the mark of a great thinker and author. We don’t just learn from great authors. They raise our head above the water to breathe again of the life the creator has given us but we have nearly drowned in our self-pitying oppressions and sorrows, or in daily mundane rhythms in which we fail to see the enchantment. My wife and I both read a lot of MacDonald’s writings, including both his classic fantasies and short stories, and his Christian novels popular in the later 1800s and early 1900s. Those writings helped to secure our souls in the divine enchantments that nourish the mundane world. MacDonald’s writing not only fed me but also opened my eyes to receive the nourishment that is always available, just beyond the natural vision.

An Inspiration

I was doing a lot of professional and technical writing when reading MacDonald’s extraordinarily poised fantasies and his pulp Christian fiction. MacDonald’s fantasies soon quietly urged me to inject a degree of story and even of allegory into those technical writings. Strings of vignettes began appearing in my thousand-page textbooks and shorter practice guides, feeding the reader’s imagination for how the dry subject might feed the lives of the subject’s practitioners. More MacDonald caused me to try writing a novel involving a professional’s challenge, paralleled chapter by chapter with a mystical allegory. I added a simple and sweet story (cover shown below) of a young couple rescuing the spirit of a desultory town. MacDonald had worked his magic. I was later off on journeys writing historical mythologies, mystery romances, and youth adventures. MacDonald had again done his work.

Theological Issues, Always Theological Issues

While the writer’s works draw general acclaim (a C.S. Lewis endorsement is a good insulator against critics), George MacDonald’s theology draws its critics. MacDonald preached enough to have his sermons gathered and published, not because his preaching drew huge crowds but because his writing did. MacDonald’s printed preaching drew its due praise, including from Lewis. MacDonald’s gift extended to the spoken word. His Boston Lyceum talks drew thousands. Yet MacDonald’s soft heart, exhibited in so many of his endearing fictional characters, turned him away from harder aspects of the good news he wished his spoken and written words to preach. Although a devout Christian whose faith reached and influenced the then-atheist Lewis, MacDonald held theological views tending toward the universalist, for which he has his theologian critics.

I don’t look to idolize anyone, not MacDonald, nor the other fascinating figures whose lives I’ve recounted the past few Fridays. I expect to find faults among them, just as I expect others to see my own many faults. MacDonald’s faults didn’t particularly reach or bother me when reading his wonderful writing. If you haven’t discovered him yet, give one of his short stories a try. And please leave your comments about what you think of MacDonald’s writings.